MENTAL HEALTH MINISTRY: PROVIDING HOPE AND HEALING

The colours symbolise peace and nature, the brain represents the mind and the hands imply care—thus giving the impression of ‘the mind in caring hands.’ (Lauren Bikhani, Mental Health Ministry Coordinator at All Saints Catholic Church, Ennerdale, Johannesburg).

Design by Warren Singh from DesignCreed.

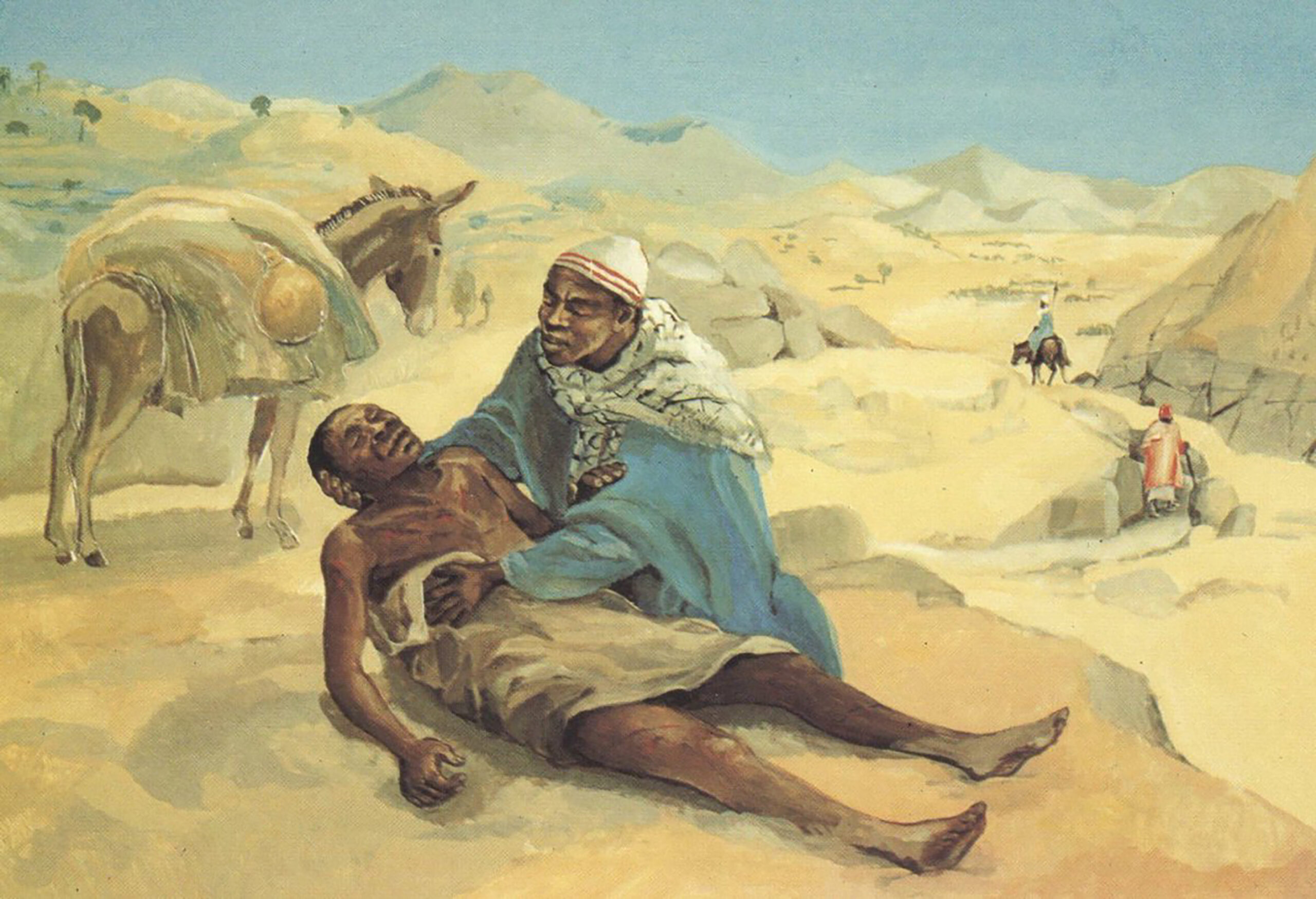

THE LAST WORD

HOSPITALITY AND FRIENDSHIP

What is the relevance of Luke’s vision of hospitality and friendship for those who are challenged by mental illness?

BY PROF. JOSHWA W. JIPP | TRINITY EVANGELICAL DIVINITY SCHOOL, CHICAGO, USA

A COMMUNITY of friends is precisely the gift that Christians can share with all people that experience deep vulnerability, stigma, and suffering. It would appear that there is a deep correspondence between the fear, exclusion, and stigma experienced by many of the characters in Luke’s Gospel and mentally ill persons today.

Christian community and friendship provide the possibility for vulnerable persons to experience meaningful relationships, relational wholeness, loyalty, and commitment even in the midst of pain and brokenness, and fellow humans who are committed to countering the stigma and exclusion many mentally ill persons experience. John Swinton has made a powerful argument that “Christian friendships based on the friendships of Jesus can be a powerful force for the reclamation of the centrality of the person in the process of mental health care” (Swinton 2000).

Person centred communities

Despite the importance of professional help offered by psychiatry and medicine, a community of friends can provide a focus upon the person (instead of the pathology) and thereby enable people “to explore issues of human relationships, personhood, spirituality, value, and community….” (ibid). Just as Jesus and his friendship overturned society’s evaluation of tax-collectors, women, the poor, and the sick so the church as a community of friends is able, through its friendship with the mentally ill and other vulnerable and marginalized peoples, to witness to a new, kingdom-oriented standard of evaluating one another.

One of the common refrains from people who struggle with mental illness is the challenge their behaviour often presents to their friends and family. How should they interact with their loved one in the hospital? Why does their friend/loved one seem unpredictable and/or resist opportunities for social engagement? Could the erratic behaviour of their loved one result in harm? Why does their loved one seem sad, angry, timid, etc., at all the wrong times?

The challenges these questions pose to friends and family almost certainly have no real satisfying answers. Persons with mental illness are not problems to be solved, but persons that require faithful, loyal, persistent, not-easily-offended friends who are willing to simply be with them.

Being with

Samuel Wells has argued that the most faithful form of Christian witness is what he describes as “being with” (rather than working for or working with), precisely because God’s act in Christ is an act of the restoration of “being with” his people; it is an overcoming of the alienation between God and humans that is fundamentally an act of hospitality that results in friendship (Wells 2015). This is a helpful way of conceptualizing the church’s engagement with those with mental illness (and those with other forms of vulnerability and suffering). Rather than treating the person as a “problem” that needs to be fixed and needs to find victory or success, the call here is for the church to simply remain with those who are challenged with mental illness. The call is an ordinary one of friendship, presence, fellowship, and all the joys and struggles that characterize friendships with one another.