MENTAL HEALTH MINISTRY: PROVIDING HOPE AND HEALING

The colours symbolise peace and nature, the brain represents the mind and the hands imply care—thus giving the impression of ‘the mind in caring hands.’ (Lauren Bikhani, Mental Health Ministry Coordinator at All Saints Catholic Church, Ennerdale, Johannesburg).

Design by Warren Singh from DesignCreed.

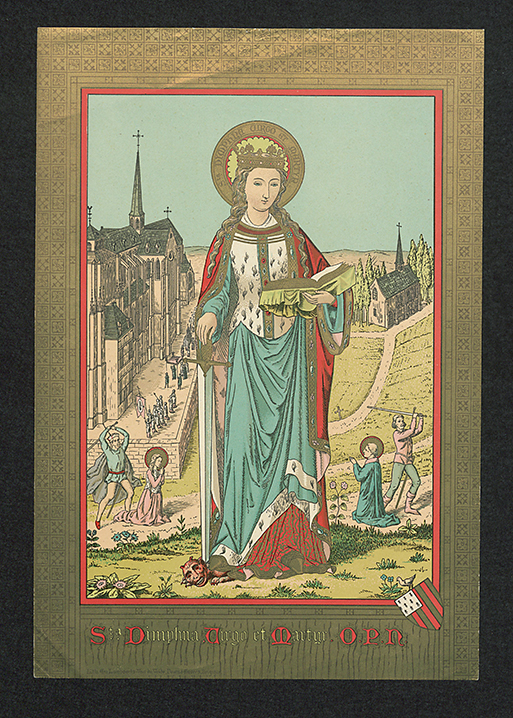

Profile • St. Dymphna

VICTIM OF MADNESS, PATRON SAINT OF MENTAL HEALTH

The tragic destiny which ended with the life of St Dymphna became a source of blessing for numerous people with mental disabilities. The place where she was martyred, Geel, a town in the north of Belgium, was transformed into a site for pilgrims. Many of them recovered their mental health through the welcoming disposition of its villagers.

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

Our modern perception of mental ill health often centers on it as a relatively new science—perhaps as a discipline conceived in the late 19th and early 20th century by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis.

In the second half of the last century, drugs to control our anxieties and various neuroses began to be prescribed—today we might say over-prescribed—in the global north. The days of incarceration in ‘asylums’ because of mental ill health were numbered. The early 21st century saw patients released into ‘care in the community’. All very contemporary—the blanket concept that in the olden days people with mental health problems were locked away; today we know how to treat them.

Historical mental health overview

Today’s research suggests that one in three women and one in five men will experience depression in their lives. Other conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are less common, but according to the World Health Organisation (WHO 2022) one in every eight people in the world lives with a mental disorder; effective prevention and treatment options exist today, yet most people do not have access to appropriate care. Harvard Medical School in the United States reports on research that predicts that in the future, one in every two people in the world will develop a mental health disorder in their lifetime. (Queensland Brain Institute 2023).

That’s the present and the future—but do we have a real picture of the past? Are we allowing modern science to blind us to the realities of mental ill health throughout the ages?

In the ancient world, there are many records of mental ill health, often ascribed to demons, and in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) we see Job, King Saul, David, Daniel, and Nebuchadnezzar all either suffering from mental ill health or dealing with others suffering a range of mental problems, from mood swings to insanity. Some of those affected by ‘demons’ cast out by Jesus would have been suffering from mental ill health.

Hippocrates (the Greek physician who lived from around 460–370 BC and gave his name to the Hippocratic Oath taken by physicians) can be regarded as quite an expert on mental ill health. He had a rational understanding of the mind and its disorders. He laid the ground rules for its clinical observation and gave importance to the idea that biological factors influence our mental health.

Then, from the 1st to the 7th centuries AD, medical writers (mainly Greek and Roman) went on to describe illnesses of the mind and recommend therapies.

We know that there was a surprising amount of traffic in those early Christian centuries between the Celtic countries of Ireland and Scotland and countries in what we now refer to as Europe—and there can be no doubt that the theories of these medical writers reached far and wide.

And that’s where the patron saint of the nervous, emotionally disturbed, and mentally ill enters the picture: St Dymphna.

Beginning of Dymphna’s life drama

Dymphna was Irish—the daughter of a pagan king who ruled part of the island of Ireland in the 7th century. Her Christian mother was reputed to be very beautiful. The mother had her baby daughter baptized, but died when the child was just 14 years old, leaving Dymphna motherless and unprotected from a father who was demented by his bereavement.

The king’s attendants were no experts in dealing with mood swings and depression and could only suggest that he ease his broken heart with a second marriage. He agreed to this and sought out a bride, but there was no woman he could imagine replacing his beautiful first wife. His advisers had the skills of neither Hippocrates nor Freud and the best advice they could now offer was that he should marry his daughter, Dymphna, who had grown to be the image of her very good-looking mother.

He was at first reluctant, but then accepted the idea and told Dymphna what he had in mind. She was horrified, and with the help of her priest, Fr Gerebern, she fled the country, sailing to the city of Antwerp in what today is Belgium. The two were accompanied by her father’s court jester and his wife (who clearly didn’t approve of the king’s plan). They soon found refuge in the small village of Geel a few miles from Antwerp port.

Sanctuary for the sick

They say—and the story of Dymphna’s life is built on legend—that while she was living in Geel, in hiding from her father, she built a sanctuary for the sick. The money that she had with her when she fled Ireland was, however, what in the end betrayed her. Her father, no doubt still suffering from his grief and anger, sent out men to track down his daughter and Fr Gerebern. When the men pitched up in Geel, they paid for their accommodation with coins that the innkeeper recognized as being the same as those Dymphna used. Unaware of the danger he was putting her in, he mentioned in conversation the young woman who must surely come from the same country as these fellows.

They of course sent word straight back to her father, who traveled from his kingdom to Geel as quickly as the boats of the day could make it. We can only imagine the mental state of father and daughter. We are told that at first, he kept his anger in check, but the more Dymphna said she would rather die than lose her virginity to her father, the less control the king had. Raging mad, he ordered his men to kill Fr Gerebern and Dymphna. Whatever their code of conduct was, they followed the order to kill the priest but couldn’t take the life of the king’s daughter.

Dymphna’s martyrdom

The king was surely suffering a bout of madness to be able to seize his own sword and cut off his daughter’s head. Her body and that of Fr Gerebern were looked after by the local people, who had developed a great love for Dymphna during her stay in Geel. Her burial site became a shrine visited by those suffering from mental ill health and many claimed that their mental, emotional, and neurological afflictions were cured by her. The Church recognized these miracles, and she was canonized in 1247.

The fame of her interventions of course spread widely, and her sanctuary was inundated by visitors. This is where the Dymphna story becomes one that confirms a very different history of mental ill health to the one, we are sold today by pharmaceutical companies, profiting from the huge number of people who experience some form of mental trauma.

A welcoming pilgrims site

When Dymphna’s sanctuary began to overflow with guests or boarders (never ‘patients’), the townspeople began taking people into their own homes. It became a tradition that lasted for centuries, and even today, people are welcomed into the homes of Geel’s residents as boarders and integrated into the community. A very ‘modern’ concept of how to care for those suffering from mental ill health— ‘treatment’ which evolved in the Middles Ages and is still the focus of the medieval church dedicated to St Dymphna.

For over 700 years, Geel’s residents have accepted people with mental disorders, often very severe, into their homes and cared for them. There are around 250 boarders today who first visit the psychiatric hospital in Geel that manages this programme. After treatment and evaluation, these guests or boarders are paired with a family in town. This is often far from easy, but the tradition of accepting mental ill health in the town is, according to researchers, responsible for the success of the programme.

It has, after all, stood the test of time. Over the centuries (and now with the backing of Geel’s 21st-century psychiatric hospital), residents have learned how to accept eccentric and disruptive behavior and they themselves have been creative in managing and helping their house guests.

Today, those who take people with mental health problems into their homes are given a government grant and receive training and support from psychiatric professionals. Dymphna’s father would not have been accepted on the programme because of his violent behavior. Nevertheless, studies show that boarders admitted to the programme are very rarely subsequently violent.

The Geel experience

It is a wonderful programme, copied today in many parts of the world. The admiration of Geel’s ability to integrate people with mental ill health into their community is not new, of course. Back in the 1860s, a visiting French doctor wrote about it. Fast forward a century and American psychiatrist Charles D. Aring reported to the journal JAMA Psychiatry, “The remarkable aspect of the Geel experience… is the attitude of the citizenry.” (Chen 2016)

In language that we certainly would not use today, mid-19th-century psychiatrists such as Jacques-Joseph Moreau said that to the people of Geel, “…treating the insane, meant to simply live with them, share their work, their distractions… In a colony, like in Geel, the crazy people… have not completely lost their dignity as reasonable human beings.” (ibid).

It all began with that little sanctuary built by St Dymphna. By the 14th century, the church where her remains are kept had become a place of pilgrimage for people from all over Europe, who brought loved ones to Dymphna’s shrine in the hope that their mental distress would be cured. Living with local farmers in this agricultural area of Belgium, the boarders would join in laboring in the fields. John Sibbald, a Scottish psychiatrist, visited Geel and wrote in 1861 “One of the agreeable features is the general contentment manifested by the insane” (ibid)—again, language we would not use today. Several establishments founded in Scotland in the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century focused on creating that contentment through labor—on farms created for the purpose of emulating the Geel experience.

Living with local farmers in this agricultural area of Belgium, the boarders would join in labouring in the fields.

The tradition of boarders has to an extent diminished with industrialization, but what has never diminished is the connection between St Dymphna and mental ill health. Many churches and shrines are dedicated to her, including that most iconic, St Dymphna in Geel itself. We remember her on her Feast Day, May 15, and we seek her intercessions as the patron saint of nervous disorders, mental disease, depression, and domestic abuse.