ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: BLESSING OR CURSE?

The image, according to Chat GPT, features the phrase “ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE” at its centre, overlaid on a stylized depiction of a microchip and circuitry. This design symbolizes the integration of advanced AI technologies within modern electronic systems, emphasizing the critical role of AI in driving technological innovation and enhancing computational capabilities across various industries.

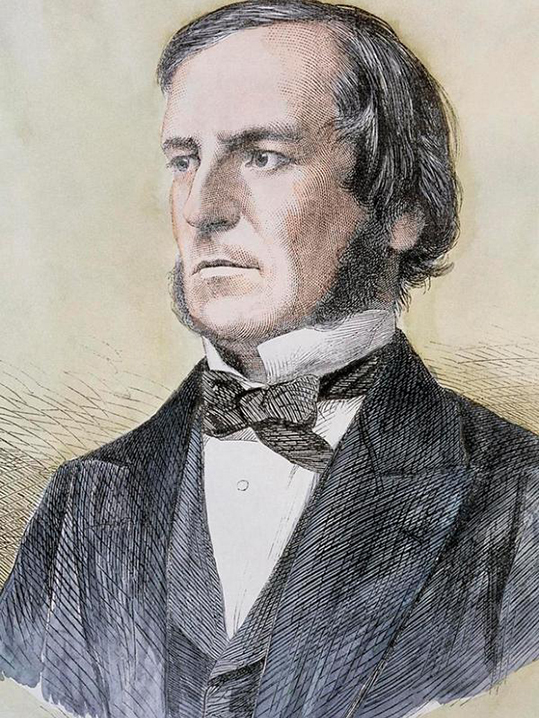

PROFILE • GEOFFREY HINTON

MORAL CONCERNS OF A GENIUS

Geoffrey Hinton, considered the godfather of Artificial Intelligence (AI), is now warning about the risks inherent in possible further developments of AI. He is determined that this powerful tool becomes instrumental for the progress of humanity and not a threat to its existence.

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

WHEN A man whose life’s work has led him to the top of his profession, highly respected by peers and rivals alike, decides to go public and question the ethics of everything he has worked for, it perhaps would be wise to sit up and take stock of the situation.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is moving forward at a whirlwind speed. Those of us who don’t quite understand how it works or what it is capable of, have until very recently been treated with patronizing disdain by scientists—and indeed, by those politicians who have seen this as a bandwagon worthy of jumping on in order to gain votes. Our fears of a future in which AI will take over, have been dismissed. AI, we have been told, can only serve to enhance our lives, not to take over the world as in the script for a B-list sci-fi movie.

Shift in humanity’s stage

But now Geoffrey Hinton, dubbed the Godfather of AI, warns that the processes he has developed could prove to be an “existential threat” to humanity. He has warned that AI could easily end up manipulating humans—or even replacing them. Let’s not underestimate humanity. God has given each one of us a brain operating on eighty billion neurons which share a hundred trillion connections. However, Hinton warns that if we allow the development of AI to proceed at its current breakneck speed, we may be kept on merely to staff the power stations, while AI renders us redundant and expendable.

“I think it’s quite conceivable that humanity is just a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence,” Hinton told journalist Sara Brown (2023). Hinton is now 76 and has made a fortune from contributing to the creation of AI. Why bite the hand that has fed him and enabled him to buy a secluded Canadian island where he is living out semi-retirement in his own rather eccentric manner?

Outstanding science background

His has been a remarkable journey, and perhaps that should not in any way be surprising: he comes from a remarkable family. The neural net pioneer—the jargon phrase that means he has contributed significantly to allow AI to reach this threatening stage in its development—was born on 6 December 1947. His full name is Geoffrey Everest Hinton, and yes, there is a connection with the highest mountain in the world. His great-great-grandmother was the mathematician and educator Mary Everest Boole, whose uncle was Sir George Everest, British Surveyor General of India in the mid-1800s, after whom Mount Everest was named. Mary Boole’s husband (great-great-grandfather to Hinton) was the logician George Boole, whose work contributed to the firm foundations of modern computer science.

As if that was not enough of a positive gene pool to give Geoffrey Hinton a head start in life, a great-grandfather was the mathematician Charles Howard Hinton, who explored the concept of a fourth dimension. He married Mary Everest Boole’s daughter Mary Ellen, and their eldest son, George, became a mining engineer and botanist who managed a silver mine in Mexico, collecting, as a hobby, new botanical specimens for Kew Gardens. His son, Professor Howard Everest Hinton, grew up in Mexico and was an entomologist studying beetles. He married Margaret Clark, had four children, one of whom is our Geoffrey Everest Hinton. As suggested, this gene pool was surely bound to lead to Geoffrey Hinton having a remarkable career, yet after leaving school (Clifton College in Bristol, England), he couldn’t make his mind up about which path to follow.

Entering the computing world

At King’s College, Cambridge, he swapped courses several times, studying natural sciences, the history of art, and philosophy. When he graduated in 1970, it was with a Bachelor of Arts in experimental psychology. He went on to complete a PhD in artificial intelligence at Edinburgh University in Scotland, and then worked at the University of Sussex.

Hinton’s great-great grandfather was the logician George Boole, whose work contributed to the firm foundations of modern computer science

However, finding funding for his work in the UK was difficult, so he headed for the US and worked at the University of California and Carnegie Mellon University. Against the background of a lack of funding in the UK, he became a founding director of the Gatsby Charitable Foundational Computational Neuroscience Unit at University College London, and then became a computer science professor at Toronto University. In June 2024, he took up the position of advisor for the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research’s Learning in Machines and Brains program.

There have been, as can be imagined, many research projects and many awards, and in 2012 Hinton set up his own company, DNN Research Inc in the Great Lakes (he holds dual British and Canadian nationalities). This was an AI, image recognition, machine learning, memory perception, and symbol processing operation, which Google bought in 2013. Hinton said then that he would “divide his time between his university research and his work at Google.”

In these fields, he has written or co-written over 200 peer-reviewed publications. His “Godfather of AI” title is well-deserved. His generosity towards many students merits him his “Godfather” role to today’s neuroscientists and operators in the neural net. He relied on gut instinct to identify those studying under him, and even those merely knocking on his door to ask questions, whom he believed would contribute to and succeed in the field of AI.

Doubts about AI

And yet, in May 2023, he announced to the world that he was resigning from Google. His decision was based on a premise that was quite remarkable considering his career: he said he wanted to “freely speak out about the risks of AI,” adding that a part of him now regretted his life’s work.

Among the many awards and accolades received during his lengthy career, Hinton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1998. The certificate of election for the Royal Society reads:

He has taken this moral stance because he knows that AI might very soon develop a brain capacity way beyond our human one.

“Geoffrey E. Hinton is internationally known for his work on artificial neural nets, especially how they can be designed to learn without the aid of a human teacher. He has compared effects of brain damage with effects of losses in such a net, and found striking similarities with human impairment, such as for recognition of names and losses of categorization. His work includes studies of mental imagery, and inventing puzzles for testing originality and creative intelligence. It is conceptual, mathematically sophisticated, and experimental. He brings these skills together with striking effect to produce important work of great interest.” (cf. https://royalsociety.org/)

Of course, the progress of that “important work of great interest” has escalated in the past quarter of our current century. Hinton’s fears about the risks of AI are now based on the runaway speed of today’s developments, which he suggests means that AI can today join up the dots, make the connections, reach its own conclusions and act upon them. If AI can achieve that today, what about tomorrow? Science fiction becomes scientific fact.

New generation of AI

Hinton now believes that what he calls “general-purpose AI” is too close for comfort. In 2023, he told the US broadcaster CBS that the timescale could be less than two decades before AI could bring about changes comparable with the industrial revolution or the advent of electricity. Interviews with him since then suggest that such changes could be even closer at hand, which is why he partly regrets his life’s work.

He has taken this moral stance because he knows that AI might very soon develop a brain capacity way beyond our human one. Chatbots, he says, can now accumulate knowledge far beyond the capacity of any individual (Kleinman Zoe & Vallance Chris 2023).

He has gone as far as to say that AI could “wipe out humanity,” and he is concerned that there are those who even now could misuse AI to create lethal autonomous weapons, saying in a May 1, 2023, New York Times article that “it is hard to see how you can prevent the bad actors from using [AI] for bad things.”

As worrying as Hinton’s latest stance is, it is interesting to see the working of his own “neural pathways.” As recently as 2018, he was still arguing that AI would not make humans redundant. But it seems that in this field, seven years is a lifetime, and his stress today results from the speed with which developments are being made: developments that could see people losing their jobs, being consigned to ‘drudge work,’ and facing poverty.

This echoes what Pope Francis said about AI in June this year when he acknowledged the ambivalence surrounding AI, saying it could inspire excitement and broaden access to knowledge around the world. “Yet at the same time, it could bring with it a greater injustice between advanced and developing nations or between dominant and oppressed social classes.”

Despite his aversion towards all faiths and his work that could so very soon threaten the world, Hinton has proved not only in his professional life but also in his personal situation that he is compassionate and follows a moral compass.

Hinton’s life thrusts

Professionally, all those PhD students whom he has nurtured and inspired would agree that he is a man of generosity whose first consideration has been to promote them ahead of himself.

Hinton has proved not only in his professional life but also in his personal situation that he is compassionate and follows a moral compass.

Personally, he has endured several tragedies. His second wife, Rosalind, died of ovarian cancer in 1994 and his third wife, Jackie, also died of cancer in 2018. For the past five years, Hinton has been with Rosemary Gartner, a retired sociologist who has said, “I think he’s the kind of person who always needs a partner.”

Hinton still seems determined to make AI a positive in our lives, posting on 19 June this year on the X platform of social media, “I’m excited to share that I have joined the advisory board of Cusp AI who have today come out of stealth mode and are using cutting-edge AI to tackle the most significant challenge of our time: climate change. …This is exactly the kind of work that I hope AI will do for us all.”

So, why the change in his stance in such a short time? It seems that despite his age and semi-retirement, he is still a work in progress. Hinton needs time to allow the eighty billion neurons in his brain to fully join up the dots and give him some answers about where AI might end up.

What may well be concerning is that, while his work continues, his fellow “Neural Net Godfathers” Yoshua Bengio and Yann LeCun appear not to be alarmed about AI’s potential in the way that Hinton is today.