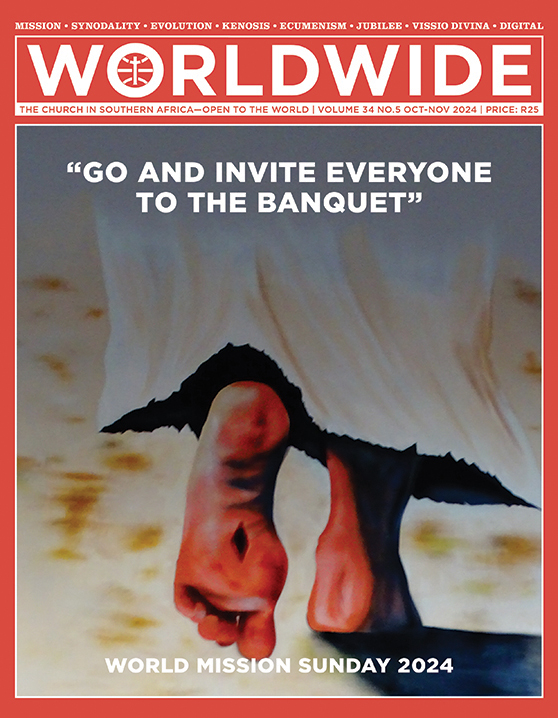

“GO AND INVITE EVERYONE TO THE BANQUET”

The image represents the feet of the Risen Jesus, in motion, showing the wounds of his Passion, yet ready to reach out and invite all to the banquet of his mercy. Likewise, Jesus invites to us to his mission in co-responsibility to bear witness to the power of his resurrection and to bring Jesus’ message of peace and fraternity to the whole world.

SPECIAL REPORT • EVOLUTION

MISSION FROM AN EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE

This short reflection will briefly sketch how Christian mission is not only compatible with an evolutionary perspective, but how it can be greatly enhanced by evolutionary theory, even provide a more exciting commitment for Christians to make in today’s world.

BY FR STEPHEN BEVANS SVD* | CATHOLIC THEOLOGICAL UNION AT CHICAGO, USA

TODAY, RURAL Semitic images and Greek metaphysics from the past are being set aside through an understanding of galactic process and stellar unfolding. Religions cannot simply repeat static scriptures and dogmas; they may often welcome new facts from science…. Science and religion are mutual truth seekers. (Thomas F. O’Meara, 2024: xii) Darwin has altered our understanding of almost everything that concerns theology. (John F. Haught, 2010: xv)

These quotations from two contemporary Catholic theologians point to the importance of taking cosmic and biological evolution seriously in theology today, as well as the radical implications of evolutionary thinking for the whole of the theological enterprise. If this is true of theology in general, it is also true of the theology of mission.

Mission and dynamism

From an evolutionary perspective, mission begins not with the call of Abraham, the sending of the disciples, or their transformation at Pentecost, but 13.8 billion years ago, at the very dawn of creation, at the “Big Bang” itself. In a famous passage of his book, physicist Stephen Hawking (1988: 174) asks the haunting question: “What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes them a universe for them to describe?” “Science rightly sees the emergence of the new,” writes Australian theologian Denis Edwards (2014: 79) in answer, “as something it should seek to explain at the empirical level, without theological interference. But this emergence is also rightly seen by theology as God-given.”

From an evolutionary perspective, mission begins 13.8 billion years ago, at the very dawn of creation, at the “Big Bang” itself.

And so, we can say, from the first moment of creation’s existence—in a kind of an intertwining dance of Holy Spirit and Divine Word—the Triune God in mission works to woo, persuade, attract, and love the universe towards its completion. Edwards speaks of the Spirit as “the energy of love” and the Word as “the divine attractor” (2014: 74-87). This dance of mission energizes and attracts “the emergence of the first particles of the early universe, … the birth of galaxies and stars, … the development of our solar system around the young Sun, … the origin of the first microbial life on Earth, … the flourishing of life in all its diversity, and … the emergence of humans with their capacity for consciousness and interpersonal love…” (2014: 79) and their yearning for transcendence and meaning in their lives, developing into the world’s various religions.

The risk of love

The Triune God’s dance in mission is not one of working from the “outside,” but rather one of immanence, the work, theologian Elizabeth Johnson writes (2014: 159), not of a monarch but a lover. From the very first moment of created existence, the Triune God through the dance of Spirit and Word, endowed every particle of creation with freedom, and thus took the risk of creation and humanity going awry, as they of course eventually did. But it was the risk of love, and the Triune God continued to be present, persuading, wooing, and healing as an active but freedom-respecting and patient partner in the divine dream of bringing creation to its completion and full flourishing. The freedom and non-determination of creation is key in both comic and biological evolutionary theory, and it entails the reality of God’s suffering—suffering not so much out of weakness or deficiency but out of the fullness of love (Kasper, 1983:196-197 in Edwards, 2014:100).

Within an evolutionary perspective, theologians speak of ‘deep incarnation’, meaning that “the incarnation is a cosmic event.”

One of these religions that emerged with human consciousness was that of the people who eventually became the people of Israel, chosen to partner with God in bringing a blessing “to all the peoples of the earth” (Gen 12:3). Through Israel’s history we can trace the missionary dance of the Spirit and the Word, as breath that breathes life into the first “earth creature” (ha ‘adam—Gen 2:7), as oil anointing the prophets to proclaim good news, healing, liberty and release (Is 61:1-2), as wind blowing over a valley of dry bones to bring new life (Ezek 37), as water gushing out of the temple to bring refreshment and healing (Ezek 47), as Lady Wisdom preaching repentance in Israel’s city streets (Prov 1:2-23), as the God who promises a new covenant with a new heart and a new spirit (Ezek 36:22-32).

Jesus’ incarnation and mission

And then, “in the fullness of time” (Gal 4:4), by the power of the Spirit, the Word became flesh (Jn 1:14), in Jesus of Nazareth. Although the significance of this incarnation would only become clear years later, the fact of the Word becoming flesh revealed the very nature of God as self-emptying love. It was in such self-emptying that the Triune God revealed the way of the divine mission. Within an evolutionary perspective, theologians speak of ‘deep incarnation’, meaning that “the incarnation is a cosmic event” (2014: 197). As Elizabeth Johnson expresses it eloquently, “[t]he atoms comprising his body were once part of other creatures. The genetic structure of the cells in his body were kin to the flowers, the fish, the whole community of life that descended from common ancestors in the ancient seas” (2014: 197).

In Jesus, the missionary dance of Word and Spirit continued, as the Spirit was lavished on him at his baptism and remained with him throughout his ministry. In him, God’s mission continued, as he embodied, demonstrated, and proclaimed the divine dream of the completion of creation, what he called the reign of God. Jesus’ mission was one of forgiveness and mercy, of healing and liberation, revealing the loving, inclusive, patient, self-emptying and freedom-respecting God who gives life and sustains all creation in being. Jesus lived out this mission in the Roman-occupied land of Palestine, and his ministry greatly threatened the Roman authorities and their local collaborators. They successfully plotted his state execution, and thought that they were done with him.

Commissioned

But they were greatly mistaken. Although all of his followers—except his mother, a few women, and one of his inner circle of Twelve—had abandoned him, three days later his scattered disciples began to experience him as alive. In a radical act of forgiveness and acceptance of their weakness, in a manner befitting the God of all creation, Jesus now lavished on them the same Spirit that had been lavished on him at his baptism, sending them forth as his father had sent him (Jn 21:21). This commission was ratified by the dramatic descent of the Spirit at Pentecost, and its significance was gradually revealed as the Spirit guided the early Jesus community to recognize its mission “to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8; Bevans, 2024: 53-84).

And so, the Church was born, missionary by its very nature, a partner with the Triune God, sharing and continuing Jesus’ work for the completion of God’s creation. Like Jesus, the Church must be open to the Spirit as it encounters new lands, new cultures, new worldviews, new knowledge like cosmic and biological evolution. Like the God Jesus revealed, it must be a Church of dialogue, of self-emptying love and of healing, a Church that respects human freedom and the beauty and wonder of creation. The Church in mission embodies, demonstrates, and proclaims the God of Jesus Christ to the world, a God who, in Jesus’ incarnation, “eternally binds God’s self to flesh and matter” (Edwards, 2014 :59).

- Stephen B. Bevans, SVD, is a priest of the Society of the Divine Word and professor emeritus of mission and culture at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. He was a member of the World Council of Churches’ Commission on World Mission and Evangelism from 2014 till 2022. He has edited and written some twenty books and serves on the editorial board of the International Review of Mission.