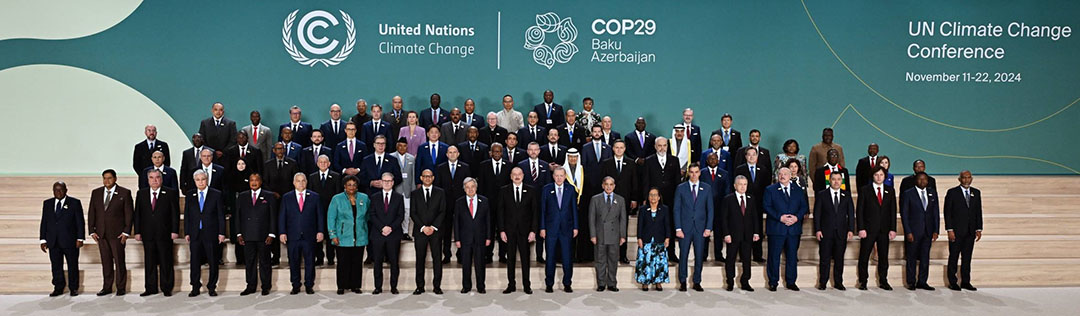

FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

RADAR

ILLEGAL MINING CLAMPDOWN IN SOUTH AFRICA: TREATING DESPERATE PEOPLE LIKE CRIMINALS IS AN INJUSTICE

BY TRACY-LYNN FIELD* | PROFESSOR OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SUSTAINABILITY LAW, UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND

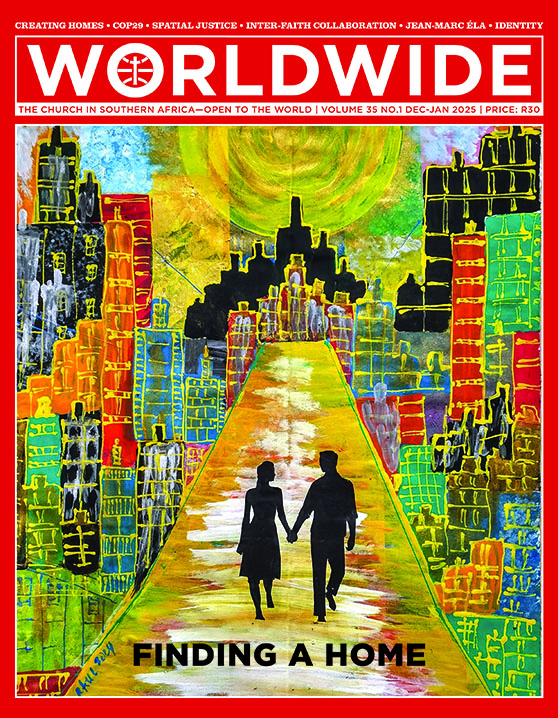

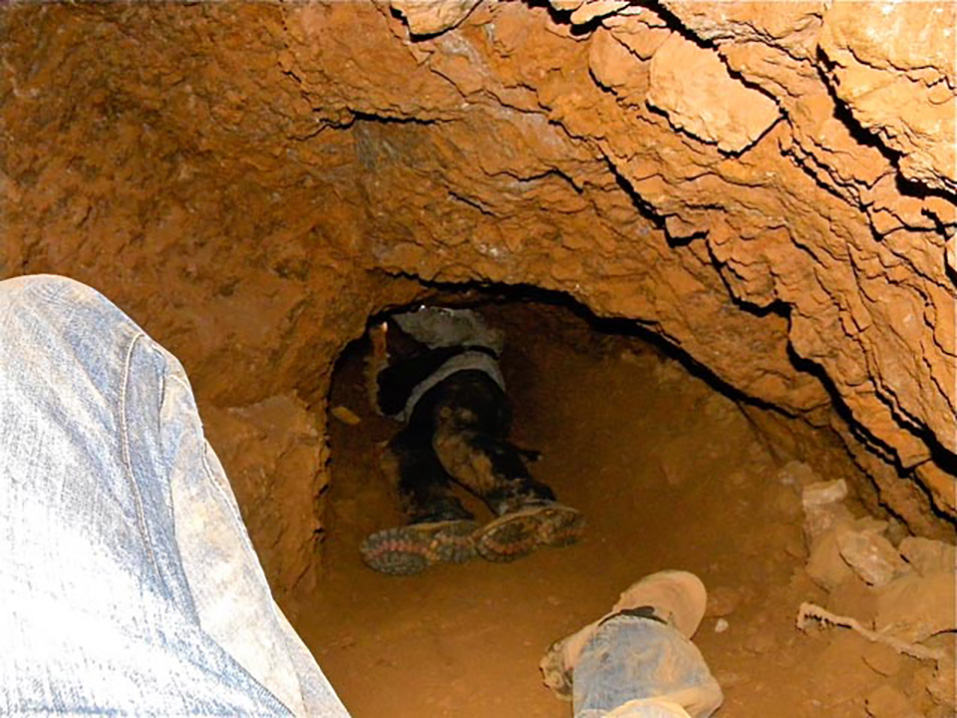

Illegal artisanal gold mining in South Africa is in the spotlight again. Under Operation Vala Umgodi (“plug the hole”), South African authorities have since December 2023 been trying to disrupt the illicit gold mining economy by cutting off water, food and other supplies to the miners working underground.

This operation is an attempt to “enforce the authority” of the state, after a series of criminal incidents in 2021 which forced the government to confront the illicit gold trade as a threat to national security.

Criminalization

In my view, the government’s approach, which sees all artisanal mining as criminal, is inappropriate because it ignores the context in which artisanal mining occurs:

- local, national and regional structural poverty (poverty as a systemic rather than an individual issue) and unemployment that will ensure a constant flow of individuals willing to pursue artisanal mining as a livelihood strategy

- an entrenched network of buyers and sellers that channels artisanal gold into the illicit trade

- an insatiable demand for gold.

The illicit trade of gold from artisanal and small-scale mining is now seen as a threat to international security. The World Gold Council estimates that as much as 20% of annual gold supply and 80% of gold mining employment comes from a supply chain controlled by criminal gangs and armed groups, abetted by corrupt governments.

The council has called on governments, international bodies and the gold sector to counteract the exploitation of artisanal miners and to prosecute criminals, preventing illicit profiteering and integrating “responsible” artisanal and small-scale mining “into the legal and viable supply chain”.

Legislation

TThe South African government has repeatedly characterised the artisanal miners, known as zama zamas (hustlers), as criminals. In my view, this narrative of criminality—when applied to artisanal mining as a livelihood strategy—is dangerous and unjust. It will do little to resolve the problem of the residues of gold on the Witwatersrand basin, straddling the Gauteng, North West and Free State provinces.

There are currently no legitimate means to becoming an artisanal miner in South Africa. Mining legislation only allows for large-scale mining and “small-scale mining”. Small-scale mining is where the mineral in question can be mined “optimally” within two years. The area must be mined under permit, and may not exceed five hectares. All other forms of mining are illegal and an “offence” under the law.

However, small-scale mining is a misnomer. The cost of cutting through the red tape to get a mining permit puts this out of reach of the vast majority of South Africans.

In 2022, the government proposed an artisanal and small-scale mining policy as a step towards formalising the sector. However, the policy failed to address several “grey areas”. These include whether artisanal mining permits could exceed five hectares, and whether large-scale mining rights could also be granted for areas designated for artisanal mining.

The government’s proposals have not been put to work through amendments to the mining legislation. This policy would be of little help to artisanal and small-scale gold miners because “artisanal mining”, as defined, is limited to rudimentary mining methods to access mineral ore “usually available on surface or at shallow depths”.

The crime of illegal mining is therefore a statutory offence and will likely remain so until the 2022 policy is revisited. When zama zama miners commit harmful and anti-social crimes, such as murder, rape, robbery and theft, or even tax evasion and money laundering, they must be arrested and prosecuted. But it is unclear how the activity of artisanal mining, if formalised and regulated, could harm society.

This narrative of criminality is also unjust because upholding the rights of arrested, detained and accused persons (anyone is considered innocent until proven guilty) is a fundamental pillar of South Africa’s democracy, according to section 35 of the constitution.

Finally, the narrative of criminality is dangerous with the possible effect that their humanity may be not respected as a matter of principle. South Africa’s proud constitutional tradition rests on human dignity.

Problematic narrative

This narrative of criminality—directed at the actors at the bottom of the supply chain, artisanal gold miners—does little to solve the real problem, which is how the state should control and govern mining activities targeting the remnants of gold in ownerless, derelict or abandoned mines and then benefit from the tax revenues.

The South African state may continue “stamping” its authority on artisanal and small-scale mining as an illegal trade for years to come. But for reasons of justice, it is time to desist from labelling artisanal and small-scale gold miners as criminals.

*Tracy-Lynn Field is the author of the book State Governance of Mining, Development and Sustainability. She has co-published on artisanal mining as a livelihood strategy.

Source: theconversation.com