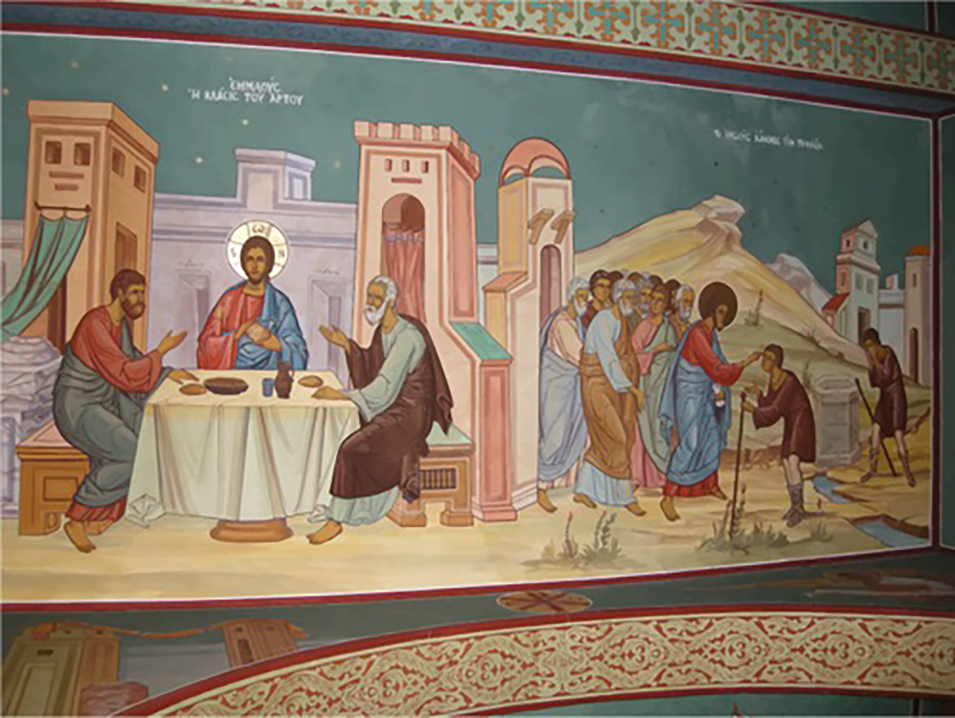

FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

REFLECTION • REBIRTH

INCARNATION AS THE ETERNAL HOPE OF LIFE

This reflection highlights how the Incarnation is a constant reminder of eternal hope knocking at our door despite the difficulties of our times.

BY FABIAN ASHWIN OLIVER | YOUTH MINISTER, JOHANNESBURG

THE INCARNATION of God is perhaps one of Christianity’s most absurd and yet powerful symbols of hope for our times. God coming, as one of us, in the condition of our time. It asks us to bear witness to a God birthed in our everyday lives, along with a life which goes beyond the cross and the experience of the grave, and into the hope of resurrection.

Sarx: God of the Cosmos

American Catholic Eco-Feminist theologian, Elizabeth Johnson CSJ, notes that in the Gospel of John (1:1-14), the Word becomes conjoined with flesh. The Greek word used here is “sarx”, meaning flesh/meat/earthly body/material. Under closer scrutiny, we can assume that the Word became flesh, not merely male or human. This signifies that the Word is embodied as a human being in unity with the world, born of a woman and within the Hebrew genealogical context. Baby Jesus represents a complex composition of minerals and fluids, existing within the cycles of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen, thereby situating him within the cosmos as a moment in the biological evolution of the planet.

The Creator God, who brings the world into existence, is united with it through the incarnation in the flesh. Therefore, the Word of God enters in solidarity not only with humanity, but also with the entire biophysical world which we depend on. The concept of deep incarnation reminds Christians of the presence of Christ throughout the natural world (Johnson 2015: 134-142).

This is resonant with the Jesuit mantra of ‘finding God in all things.’ The natural world reveals Godself and shifts us beyond our spiritualised androcentric (male centred) and anthropomorphic (human centred) understanding of God, dwelling towards a multifaceted view of God in the fibres of the cosmic order. The beauty and the splendour of springtime signify new life, similar to the birth of new-born babies delivered in hospital wards. Additionally, the groans of the earth—the ecological catastrophes that we face – along with the cries of the earth and those of the poor also signify the cross of Jesus reflected in our earthly experience.

The manger as antithesis of Power

The Christmas story portrays baby Jesus, born not in a castle or in the empire building, but in a manger—not to a royal class family, but to a teenage girl from the margins (‘he has brought down the mighty from their thrones and exalted those of humble estate’ (Luke 1:52)). Thus, the God of all comes into our condition at the site of struggle, amid poverty-stricken conditions, fleeing war and degradation, and facing inequality and despair. The manger, like the cross, can also be seen as a critique of power which kills, worsens the plight of the poor, excludes people of colour and women, and overlooks the non-human. The manger that houses non-human life (livestock and others) under the stars and planets, reminds us of the cosmic witness to God’s presence among us, re(inviting) us to the hope of life, the promise of salvation, and the liberation from the unjust world as we know it, towards God’s kingdom which is at hand.

God classically described as allknowing and allpowerful, yet coming as a baby ever so vulnerable.

Eboni Marshall Turman’s book, Womanist Ethic of Incarnation (2013) investigates the intersection of womanist thought and the concept of incarnation within the framework of Christian theology. The central premise revolves around understanding the divine incarnation through the experiences and perspectives of Black women, highlighting the significance of embodied realities and the pursuit of social justice. Turman contends that conventional interpretations of incarnation frequently neglect the lived experiences of marginalized communities, especially those of Black women. By incorporating womanist principles, she offers a reinterpretation of the incarnation as a dynamic and relational phenomenon that affirms the dignity of all bodies, while emphasizing the necessity for justice, liberation, and solidarity with the oppressed.

The incarnation gives us abundant resources of mystery: God whom we cannot fully grasp, beyond our worldly restrictions, yet born to us as one of us, confined to space and time; God the creator of all things, and lover of all people, yet embracing solidarity with all suffering and oppressed; God classically described as all-knowing and all-powerful, yet coming as a baby ever so vulnerable, in need of our safeguarding, and in a form of disruption to the powers, that be, towards an understanding of the powerless power of God.

Jesus comes to make his home with and in us. A spiritual understanding of this is to have Christ in our hearts, to be united with his everlasting love, and to be a light in the world, radiating God’s love, mercy, and peace for all to see. Jesus’ home with us also carries socio-economic shifts for our way of being. South African biblical scholar Gerald West noted that former President Thabo Mbeki utilized the Bible to shift the focus from the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which aimed to provide formal housing for the impoverished, to a spiritualized notion of housing that emphasizes personal well-being rather than the provision of actual houses. This transition from economic considerations to moral ones was formalised in the document titled The RDP of the Soul. While moral issues are indeed significant, it is crucial not to separate them from economic concerns. West also points out that many church leaders have narrowed their focus mainly to moral topics, such as abortion and same-sex marriage, unfortunately overlooking the plight of the poor and the economic initiatives necessary to alleviate poverty (Urbaniak 2017: 43).

Eternal hope

The incarnation of Godself offers us the reassurance that Emmanuel (God with us) is always birthed into the most vulnerable, hidden, tragic, and difficult parts of our lives. ‘Indeed, God is always needing to be born. The birth of Christ offers us brazen hope like a ‘fire that no one can put out’ (words famously attributed to Dr Martin Luther King Jnr’s speech the day before his assassination). This hope is intrinsic to all creatures that breathe, a testimony to the sacred or divine presence in all life.

The dwelling of Christ means we are not alone; we can build a different social order where there are adequate housing and opportunities for the poor. The ecological crisis at hand petitions us to shift our gaze from profit and consumption at the expense of our common home, towards hearing the cry of the earth and meaningfully changing our trajectory. There is overwhelming evidence that if we change our destructive modus operandi, the earth will bear new and wondrous life for all. The Prince of Peace comes with a sounding call to join in the works of peace in Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine, Congo, and many other spaces (notwithstanding, there can never be true peace or reconciliation without justice). We are called to feel the plight of the migrant and refugee, and to find alternatives for the many homeless people in our common home. The cry of all oppressed bodies is a dwelling place for God and an invitation towards a re(birth) of our context knowing that Jesus is at work through the proclamation, “Behold I make all things new” (Revelation 21:5).

There is overwhelming evidence that if we change our destructive modus operandi, the earth will bear new and wondrous life for all.

Thus, the Church becomes a place of birthing of new possibilities of freedom and life, of sharing communion and of serving others, and passionately performing works of love which are always focused on eradicating injustice. The incarnational Church offers a twofold dwelling: for the faithful to experience Christ and for Christ to dwell amongst them. Thus, the faithful should balance their mystical experience of transformation of self with the prophetic transformation of the world we live in. Today, we can find baby Jesus, the Prince of peace:

“Proclaimed in hopeful visions, promised in unlikely friendships, hidden in forgotten spaces, discovered in mysterious encounters, born in humble places, treasured by eager hearts and revealed to wisdom seekers” (Rondebosch United Church 2018).

References

Bible: New Revised Standard Version, Anglicized Catholic Edition. 2005. London: Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd.

Johnson, E. 2015. ‘Jesus and the Cosmos: Soundings in Deep Christology.’ In Gregerson, N.H. (ed.). 2015. Incarnation: On the Scope and Depth of Christology. Minesota: Fortress Press.

Rondebosch United Church. 2018. ‘Carol Service with our famous Matrushka doll.’ Available from: https://www.rondeboschunited.org/highlights-2018 (Accessed on 23 October 2024).

Turman, E.M. 2013. Toward a Womanist Ethic of Incarnation: Black Bodies, the Black Church, and the Council of Chalcedon. New York: Palgrave MacMillian.

Urbaniak, J. 2017. ‘Faith of an angry people: mapping a renewed prophetic theology in South Africa.’ Journal of theology for Southern Africa. 157:7-43.