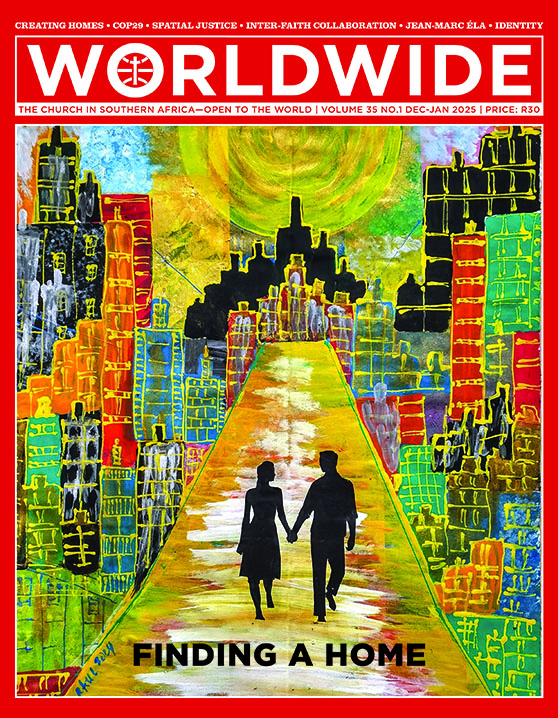

FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

INSIGHTS • ACCESS HOUSING

THE RIGHT TO HOUSING

BY MIKE POTHIER | PROGRAMME MANAGER, SACBC PARLIAMENTARY LIAISON OFFICE, CAPE TOWN

THERE IS no doubt that South Africa has a housing shortage. Every city and large town has informal settlements, some of them extending for kilometres and hosting tens of thousands of people. In some parts of the country, the so called ‘backyard dwellers’ make up a large proportion of the urban population; they live in shacks or garden cottages, often paying rent to the owner of the property.

Some people may be on the waiting list for an RDP (Reconstruction and Development Program) house or some other form of public housing; and it is not unusual to hear of people who have been on such a list for 20 years, and who seem no closer to getting their own home than when they first applied. In Cape Town, there are over 350 000 people on the city’s waiting list, and the figures are probably similar, or worse, in other big towns.

How can this be so, 30 years into democracy and with a Constitution that states in its Section 26(1): “Everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing”?

Unfortunately, the socio-economic rights in the Constitution are not as straightforward as they appear. They are formulated in a way that provides a ‘qualified right’—which may only be fulfilled partially and gradually as or when finances and other resources become available.

This may sound like a cop-out, a way for the state to avoid its obligations, but in fact it is a wise and very necessary precaution. Indeed, some countries’ Constitutions—India’s being one well-known example—do not include socio-economic entitlements in their Bills of Rights at all.

The reason for that restraint is simply that no state, no matter how wealthy, can provide housing, education, healthcare, food, water and all other necessities of life immediately and universally for all its people. This applies all the more to developing countries such as South Africa. When the Indian Constitution was drafted it was thought wise to deal with these needs by the so called ‘Directive Principles of State Policy’. Simply put, the Constitution instructs the state to develop and implement policies to satisfy people’s needs for healthcare, education, employment and social security, but it does not give the people the right to go to court to demand satisfaction of these needs.

The state cannot neglect its duty to make housing available to those who can’t afford it.

South Africa chose a different way of dealing with this issue. Our Constitution builds some limitations or qualifications into the way the right is phrased. Thus, the housing right does not imply that ‘everyone has the right to a house’; instead, it talks about ‘access’ to housing. Wealthy people can access housing simply by buying or building the house of their choice. People with stable employment can access housing by borrowing money from a bank, in the form of a bond or mortgage, and using this to purchase a house. And people who can afford neither of these options can, in theory at least, approach their municipality and be given a RDP house or what was formerly called a ‘council house’.

However, section 26(2) goes further than that—it also imposes a duty on the state to ‘take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realization’ of the right. On the one hand, this means that the state cannot just sit back and do nothing about housing; but on the other hand, as long as what the state is doing is reasonable (and there are legal texts to determine what that means), no court can instruct the government exactly what it should do, such as to build particular houses in specific places for specific people.

The phrase ‘within its available resources’ is an acknowledgment that the state has limited amounts of money and other resources available that are needed to supply housing—land, especially. It also recognises the fact that the state must also allocate money to other pressing needs, like health, education and social grants.

Therefore, nobody can simply demand to be given a house by the state. But simultaneously, it means that the state cannot neglect its duty to make housing available to those who can’t afford it. In this way the Constitution seeks to find a balance between people’s needs and the state’s constant limited ability to meet those needs.