FINDING A HOME

This painting represents the reality of so many people in the world looking for a place to stay, especially as they flock into crowded modern cities, searching for jobs or fleeing from various situations of conflict. The need to create living spaces for them is acute. Like Joseph and Mary, who found no place at the inn, millions of people risk ending up unsheltered in the streets and deprived of a dignified dwelling which they can call home.

Painting by Fr Raul Tabaranza MCCJ

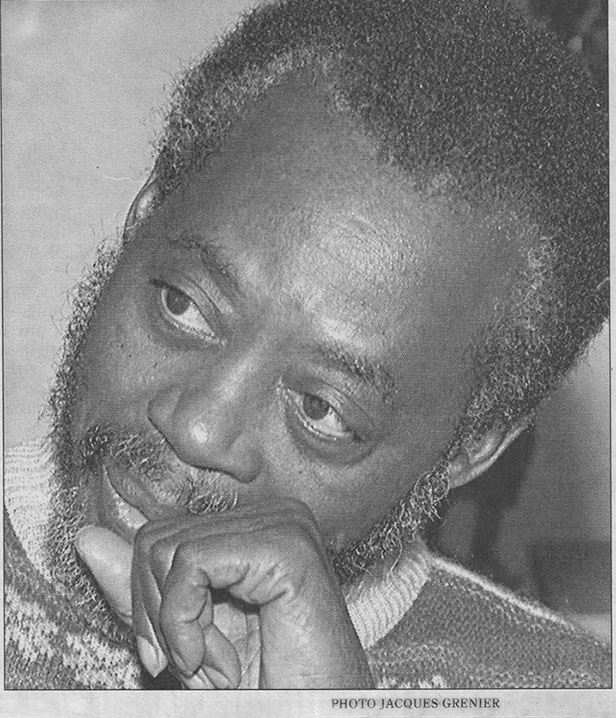

PROFILE • AFRICAN LIBERATION THEOLOGY

THEOLOGY FROM THE GRANARY

Jean-Marc Éla spearheaded a generation of African theologians who did not remain impassive when faced with the various challenges of the continent, but strived to identify their root causes and proclaim the Gospel as a force of liberation from all kinds of evil.

BY MARIAN PALLISTER | CHAIR OF PAX CHRISTI SCOTLAND

IN THE WEST, we are inclined to associate Liberation Theology with Latin America. Catholic priests there strove to make religious faith relevant to modern life by aiding the poor and oppressed through involvement in political and civic affairs. It created an awareness (very much unwanted by the rich and powerful) of what they termed the “sinful” socio-economic structures causing social inequality, and they encouraged active participation in changing those structures.

The birth of the liberation theology movement is linked to the second Latin American Bishops’ Conference in Medellin in Colombia in 1968, when the bishops issued a document affirming the rights of the poor and asserting that industrialised nations were enriching themselves at the expense of developing countries.

Gustavo Gutiérrez, who passed away on 22 October 2024, was considered the “Father of Liberation Theology”. This theology was not approved of by the hierarchy (Pope John Paul II summoned its leaders to Rome and told them that this was not official thinking) and men like Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador not only fought for an end to injustice and social inequality but died for that cause.

We have heard little, however, about Liberation Theology in Africa, or of the “Father of African Liberation Theology”, Fr Jean-Marc Éla, who sought social equality and justice for his home country, Cameroon.

Africa in miniature

Cameroon is a country recognised worldwide for its football. Nevertheless, outside of the African continent many people might not know much of its actual geographical position, history and politics. Yet it is home to around 31 million people and from the 15th century has interacted with European countries. Each brought their own range of problems to the area and plundered from the riches they found there.

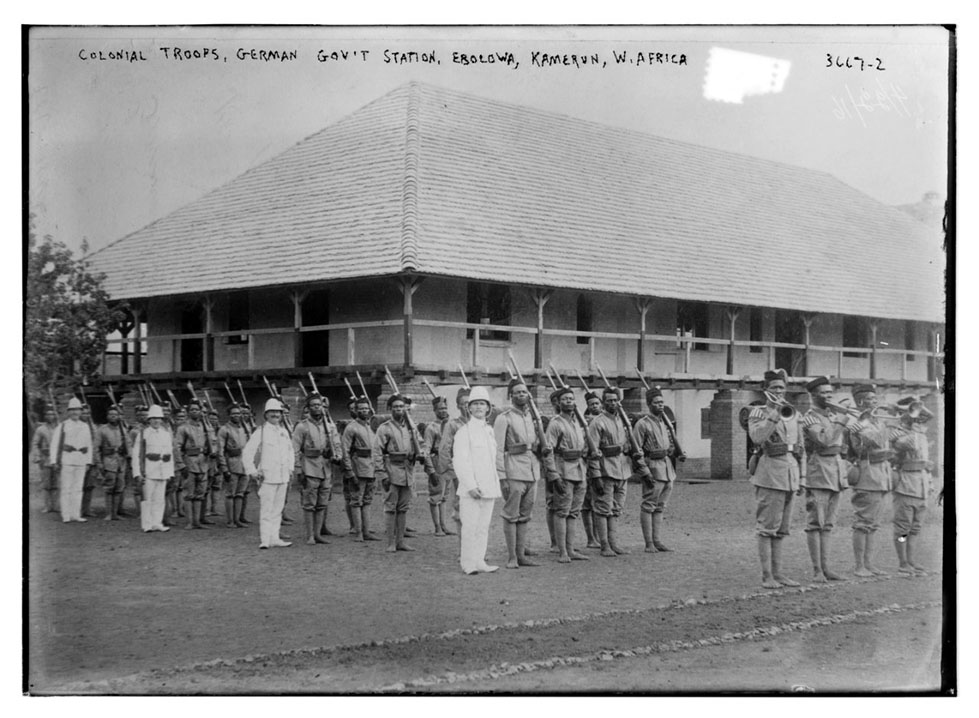

It is known as Africa in miniature because of the amazing range of terrains within its borders. The Portuguese were first to “discover” it in 1472 and gave it the name of Rio dos Camarões, or Shrimp River. The English language morphed that into “Cameroon”. The Germans colonised the area from 1884, but after World War I it was divided between France and the United Kingdom. France ruled a majority section and the UK one-fifth of the territory until the two sectors gained independence in 1960 and 1961 respectively.

As if the colonisers had not done enough damage, peace did not become a feature of the country in the ensuing six decades. That could be because of the diversity of cultures within the European-drawn borders (Cameroon has 250 languages over and above the “official” French and English national languages). It could be because the country is surrounded by states where peace is in very short supply: Nigeria (from where the British ruled their minority portion of the colony and gave it little thought), Chad, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Atlantic Ocean must surely feel like a welcome escape route.

Experiencing Home

It was in the south of the country, in Ebolowa, that Jean-Marc Éla was born on the 27th of September 1936. He attended elementary school in his village, then went on to minor seminary at Edea.

His name appeared on a hit list of people to be liquidated by the Biya regime.

was in those early years, nurtured by a typically extended family and lived out not only in the household of parents, Jean Éla and Odile Mekong, but taught the skills of the forest by cousins, that Éla’s sense of home — and the essentials of ‘home’ — were conceived and in time would become the bedrock of the sociology he would share in later life.

Those essentials were liberty, freedom to choose how life should be lived, freedom to enjoy life and the knowledge of how to endure what life might bring. He would say in later years that “coming from a family where one never passively endured injustices, humiliations, disparagement or domination, I considered myself a little like the inheritor of these cultures of resistance.”

Home during the childhood of Jean- Marc Éla, however, was never easy, punctuated as it was by the Second World War, famine, and the beginnings of political unrest.

Theology from the village

He became what is described as a ‘chamber boy’ for the foreign missionaries in his parish, and no doubt it was there that his vocation for the priesthood was conceived, although he would not be ordained until 1964.

He went on to obtain a doctorate in philosophy and theology at the University of Strasbourg, and a doctorate in sociology at the Sorbonne in Paris.

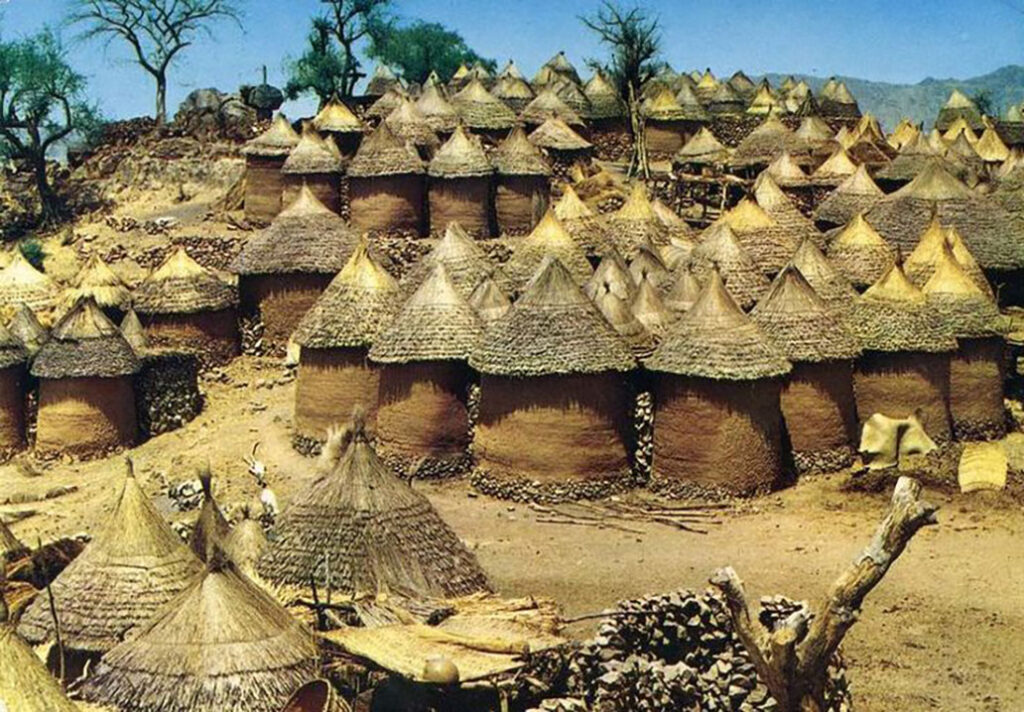

But the “education” that he received working in northern Cameroon with the Kirdis from 1971 to 1985 is undoubtedly what led him to the Liberation Theology that resulted in death threats and exile.

He would say: “…my theological reflection was born in the villages. My theology was born to be precise, under the palaver tree in the northern mountains of Cameroon. In the evenings, I gathered there with Africans of either sex to read the bible with African eyes. For fourteen years I shared their destiny and got involved in evangelising. My theology was not born between walls made of concrete” (Ugochukwu 2021).

As he developed this line of thinking and made himself the voice of the voiceless, Éla became a thorn in the flesh of the Cameroon establishment. He sought justice for the people of the country he loved—but those in authority whom he labelled as greedy and ruthless had him marked as “bothersome” and his name appeared on a hit list of people to be liquidated by the Biya regime.

He wasn’t the only one under threat. Fellow priest Fr Engelbert Mveng, who shared Éla’s struggle against oppression, was found murdered in his home in 1995. It was time to get out, and Éla fled to Canada.

A prolific writer, among his many works these stand out as representative of his African Liberation Theology: Cri de l’homme Africain (translated into English as African Cry), De l’assistance à la libération: Les tâches actuelles de l’Eglise en milieu africain (translated into English as From Charity to Liberation), and Ma foi d’Africain (translated into English as My Faith as an African).

African context

What emerges from his teachings, his thoughts, his theological journey, is that his concern for the ‘ordinary’ African— the struggling man, woman and child in his much-loved Cameroon— was paramount. His African-oriented Liberation Theology matched everything that was coming out of Latin America but was very much in the context of his own lived experience and that of the Kirdis with whom he lived and to whom he offered pastoral care.

Éla formed his theology in the streets, in the empty granaries of mothers desperate to feed their children, and under the palaver tree.

My favourite quote from Éla—perhaps because it resonates so deeply with the experiences of my friends in Zambia going through today’s devastating drought, mismanaged supply of electricity, and the terrifying rising cost of living—is that “friends of the gospel” must be conscious of God’s presence “in the hut of a mother whose granary is empty.”

That comes from his book My Faith as an African (1988), in which he also says that as an African theologian, he had to be prepared “to get dirty in the precarious conditions of village life”.

This was a man who understood the realities not only of village life, of the empty granary, but of the politics that impacted so deeply on the most remote of people; the greed of those at the top that deprived those in his pastoral care of their human rights —of the very food that Catholic Social Teaching and the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights agreed should be served from their cooking pots more than once a day.

Let us not suggest, however, that the Church had not shared in creating a two-tier society that made Africans subservient to colonial masters. Éla’s book From Charity to Liberation gives a fair idea of that particular history. In post-colonial times, it was not only the new brand of political despots who found men like Éla “bothersome”. This African Liberation Theology was no more popular with Rome than its Latin American counterpart. The big difference, of course, was that Rome only intended to rap the knuckles of the Liberation Theologists. The Cameroon dictators had much more violent retribution in mind.

In a new century, with Pope Francis —who grew into Liberation Theology in his native Argentina—at the helm, attitudes have drastically changed within the Church. Pope Francis has joint the sentiments of men like Éla, saying “I would prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its security” (Evangelii Gaudium, 49). Éla formed his theology in the streets, in the empty granaries of mothers desperate to feed their children, and under the palaver tree.

Speaking out

Pope Francis also gives approval to Christians engaging in politics: not party politics but having a voice. That change in thought was still to come when Éla was urging villagers to be vocal in the running of their community and their country. European missionaries had pushed the then current European line that politics and religion shouldn’t mix. African Liberation Theology gave everyone the dignity of expressing political thought. Éla was simply going back to Bible basics in the 1980s and ’90s, telling his flock that as they were created in God’s image, they should never be excluded from determining their own fate.

Of course, this was in an era when poverty, famine and conflict stalked Africa, and in the more affluent parts of the world the TV images were heartbreaking. Pop stars came together to raise money to “feed the world”, most specifically Africa. Éla, however, knew that charity was not the long-term solution. Liberation Theology was. He believed that concern for the poor and marginalised, the liberation of women and children, were the key that Christianity in Africa had to employ to rid the entire continent, not just his native Cameroon, of poverty, hunger and exploitation.

But how did a parish priest in a rural area of Cameroon end up with a death threat? Who was taking notice of these ideas for liberation?

Yes, his writings were taking those ideas into the wider world. He was teaching sociology at the Faculté Protestante at Yaoundé University. He also preached at a nearby parish every week in the early 1990s. He attracted hundreds of students who listened to his socially aware homilies that never failed to mention his rural roots. Social justice was always a key thread. Governments that did not provide social justice were never let off the hook.

Thus, he was labelled “bothersome”. His name appeared on the list of those to be gotten rid of, and he took that journey into exile, so that he could continue to seek social justice for his home country, his home continent.

Fr Jean-Marc Éla fled to Canada, where he lived, wrote and lectured in its universities as well as in the United States until his death in December 2008. His African Liberation Theology gained traction. Some 16 years after his death, with famine, oppression and conflict once more hurting his cherished continent, may his brand of social justice be remembered and acted on.

References:

Ugochukwu Iheanacho, V. 2021. Jean-Marc Éla’s Hut and Empty Granary: Rethinking the Social Significance of Theology in Africa. Pretoria: Church History Society of Southern Africa & Unisa Press. https://scielo.org.za/ pdf/she/v47n1/09.pdf