FINDING A HOME

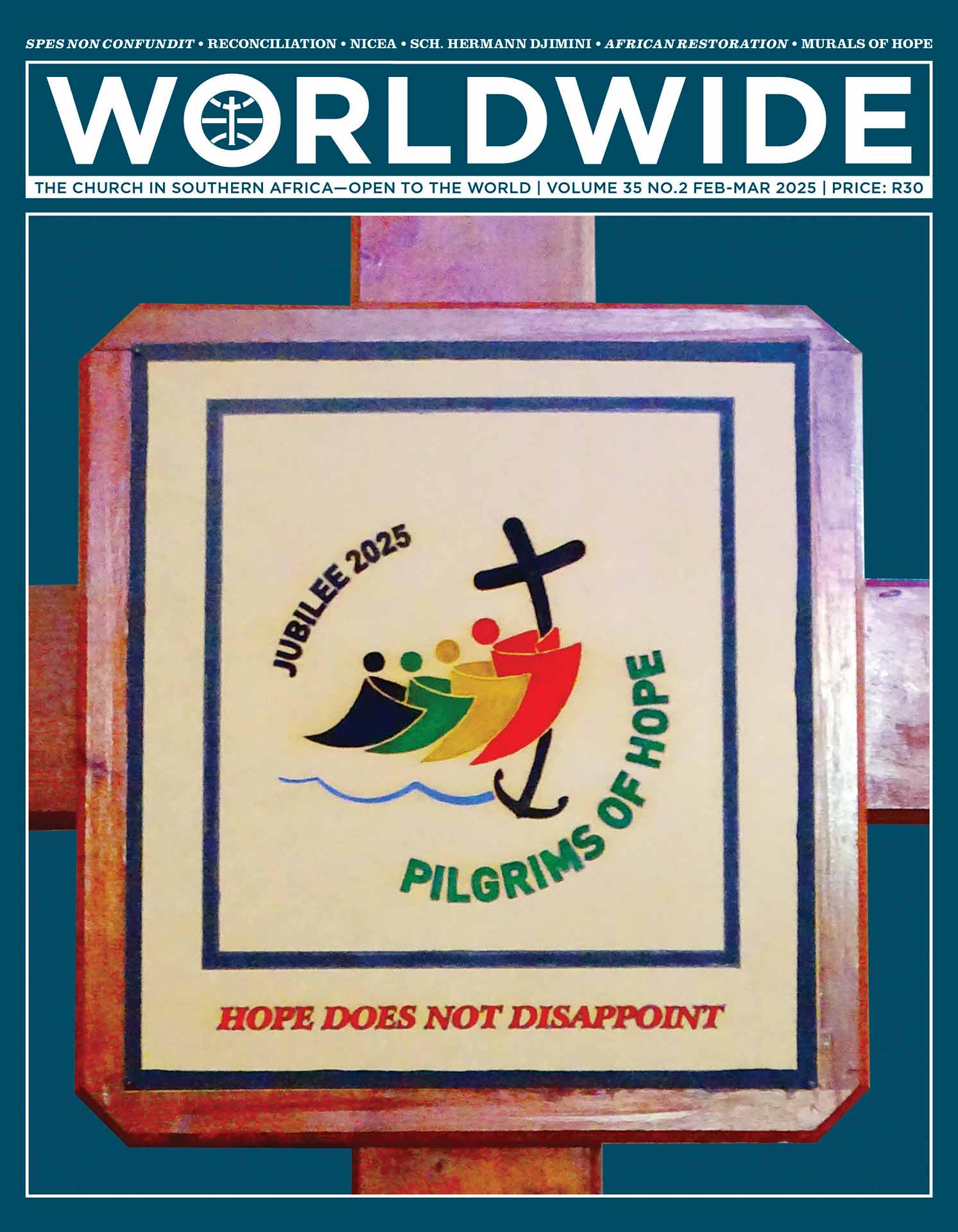

The cross is also the anchor of our hope as it appears in the Jubilee logo embedded onto the lit candle. The lower part of the cross is elongated and turned into the shape of an anchor, which is lowered into the waves and stabilizes the ship amidst the storms.

In addition, the cross is bent down backwards towards the four human figures. This indicates God’s act of compassion, seeking us out and offering surety of hope.

RADAR • MOZAMBIQUE

CHAPO’S HEAVY BURDEN: RESTORING MOZAMBIQUE’S FRACTURED SOCIAL FABRIC

BY BORGES NHAMIRRE, | CONSULTANT, ISS PRETORIA

DANIEL CHAPO, Mozambique’s recently inaugurated fifth president, inherits a nation embroiled in violent post-electoral protests which have in just three months led to over 300 deaths, and destroyed businesses and social infrastructure. President Chapo will need to reverse this political upheaval and the economic exclusion that fuelled the riots.

The violent demonstrations against the 9 October election results, coupled with the police’s brutal response, are however not the core of Mozambique’s problems. They are merely the tip of the iceberg in a divided and intolerant society in dire need of reconciliation.

The current crisis stems from former president Filipe Nyusi’s authoritarian rule, marked by systematic electoral fraud, persecution and assassination of opposition leaders, and the exclusion from governance of rival political parties and civil society.

The problem is however deeply entrenched in the unequal distribution of the country’s wealth. Indeed, the underlying causes of the almost 10-year-old violent insurgency in Cabo Delgado – socioeconomic inequalities, political exclusion and elite corruption – may also be the driving force behind the post-electoral violence across the country’s major cities.

Social cohesion in Mozambique requires pragmatic actions, including the sharing of power with the opposition.

Elites and Poor Governance

Political elites, who are also economic elites or closely allied with them, have neglected most of the population, especially the youth. While public school teachers endure months without salaries, students study without textbooks and doctors strike for increased pay, the political class enjoys a luxurious lifestyle, distributing expensive gifts and vehicles among themselves.

This disparity has fuelled resentment among newly graduated but unemployed young people, informal traders unable to sell their goods on city pavements due to police extortion, and farmers whose lands are seized by mining companies, while the government remains indifferent.

During the elections, citizens frustrated by poor governance, voted overwhelmingly for the opposing presidential candidate, hoping to bring about change. But the process was neither free nor fair, with opposition votes altered in favour of the ruling party.

Selective assassinations of senior opposition members, which characterised Nyusi’s governance over the past decade, contributed significantly to the environment of mistrust that has led to the current post-electoral violence.

Political repression

During widespread post-electoral protests, at least 100 PODEMOS party members—including two opposition leaders closely associated with presidential candidate Venâncio Mondlane—were shot and killed, most of them in their homes. There are widespread suspicions that death squads were behind these killings. In one case in Cabo Delgado, witnesses reported that the killers of a local opposition leader wore uniforms used by the government-supported Força local militia.

None of these killings by members of the police – whether of opposition leaders or civilians – have been investigated. This not only reflects the judiciary’s incapacity, but indicates that the perpetrators are protected by those with political power.

Nyusi has left a heavy burden for his successor. Chapo’s first mission must be to rebuild the fractured social fabric, regain the trust of Mozambicans, and repair a shattered society.

In his inaugural speech, Chapo claimed that social harmony was his priority and that dialogue with the opposition had already begun. He pledged not to rest until the country was united and cohesive, and on course to ensure the wellbeing of all.

Building social cohesion must however go beyond rhetoric. It requires concrete, pragmatic actions. In Mozambique’s case, this includes sharing power with the opposition, and the redistribution of wealth among the broader population.

Committed diplomatic efforts are needed to persuade the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO)—the ruling party which has governed alone since independence, manipulating electoral processes—to steer the country back towards democracy and to consider a power-sharing option, implementing meaningful electoral reform.

Economy

Another challenging task for the new president will be to reduce inequality and to focus on human development instead of enriching the ruling elite. This will require investing in better education and health, and creating job opportunities for the majority who feel excluded from the country’s prosperity.

Benefits from major exploitation of natural reserves (resources include rubies, natural gas and heavy mineral sands), must reach local populations. Nyusi’s failure to deliver on this resulted in mining companies’ property being attacked and vandalised during the post-election protests.

The SADC’s interventions to help resolve Mozambique’s post-electoral crisis must aim higher than merely resolving current clashes.

Without profound political and societal reforms, Chapo’s efforts to quell the anger and resentment will certainly hold back the solution of Mozambique’s problems. Political violence will resurface as soon as an opportunity arises, whether through an armed insurgency like the one in Cabo Delgado, or by means of public protests against fraudulent elections or any other event perceived as deeply unfair or unpopular.